Alternate poetry

Poetry as a form of literary artistry may not be the most popular pastime it once was. It’s probably also fair to say that it’s often a misunderstood concept. However, Japanese haiku poems may be the exception to these circumstances.

Compared to many other types of poems, the Japanese haiku is short and sweet, easy to understand and provides an exceptional sense of imagery to the reader. For these reasons they are arguably one of the most loved forms of poetry; while many may not actively search out haiku, coming across them provides a burst of imagination that leaves a lasting impression.

This is the wondrous nature of haiku.

Haiku form and structure

The Japanese haiku are short-form poems that consist of a total of three lines, during which, they are able to succinctly and comprehensively illustrate an entire scene. By and large, haiku do not need to rhyme, nor do they need to include a cadence or specific rhythm. This is what makes them both enjoyable to write and to read.

Despite this, there are a handful of guidelines and techniques that are employed to make haiku what they are.

Syllables and ‘on’s’

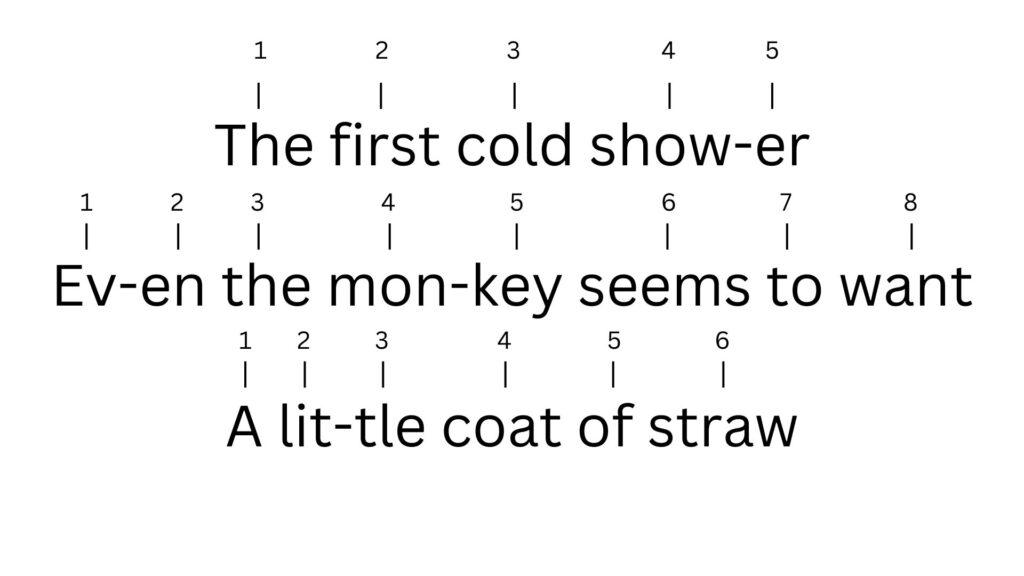

Within a haiku’s three line format, there is typically a 5-7-5 syllable pattern totalling 17 in total. This means the syllables on the first line must add up to five, the second 7 and the last line 5 once again.

This is a universally accepted definition of a haiku’s structure, although it serves more as an accessible entry point than a hard and fast definitive rule. As such, you will often encounter haiku which slightly deviate from this pattern, whether it be 6-8-5, 4-7-6 etc. While keeping in close proximity to the standard 5-7-5 pattern poems will retain the feel of being a haiku. The middle line containing the most syllables is a far more solid practice.

These variations arise most commonly from translative and regional differences. This is where we see the first contrasts with Japanese haiku poems Vs those written in English.

Japanese vs English haiku

Japanese haiku are poems that will almost exclusively follow the 5-7-5 pattern, but the way they measure that is slightly different. Rather than a syllable, an ‘on’ refers to the letters and sounds of the Japanese language; although the principle is very similar there are times when a word in English will be read as one syllable but in Japanese could be two or more.

To explain these ideas without the post becoming a lengthy Japanese language lesson, let’s use an example:

“The first cold shower

even the monkey seems to want

a little coat of straw”

Matsuo Basho

Here is the original in Japanese.

初しぐれ猿も小蓑をほしげ也

Matsuo Basho

The first thing to notice is that Japanese haiku always exists all on a single line.

Next let’s dissect each version of the haiku with a comparison in each language.

As you can see the Japanese haiku is indeed in the 5-7-5 pattern but when translated properly into English it becomes slightly longer.

For the record anyone who may not know Japanese might read the words something like this:

These examples somewhat explain why Haiku written in English may appear to deviate from the regular pattern; if you are looking up popular examples, chances are they’re originally older Japanese haiku’s.

Yet, the brilliant thing is that anyone can write them. Haiku originally written in English can follow their own 5-7-5 pattern using natural syllables, however, as we’ve seen they also work with more (or less). There is also a common methodology that involves English haiku being written with 12 -14 total syllables to replicate the succinctness of their Japanese counterparts.

haiku Imagery and subjects

While it’s certainly possible to write a haiku involving any subject matter; another prominent feature is that they will often involve natural themes and scenes.

Animals, plants, water, the moon, wind, these are the kinds of subjects that are explicitly mentioned in many Japanese haiku poems — including some of the most famous. Here is perhaps the most well-known haiku by Matsuo Basho named ‘The Old Pond’

“old pond

frog leaps in

the sound of water”

Matsuo Basho

Such is the case that natural themes make up the vast majority of subjects, that most haiku will be sorted into spring, summer, autumn, and winter poems.

Cutting word

The last key ingredient to making the perfect haiku is something called a cutting word or ‘Kireji’ in Japanese. It’s usually a ‘character’ — not an actual word — that disrupts the flow of writing and forces a lingering pause. Because of this, it is often placed at the end of one of the first two lines which also allows it to be used as a connecting element that essentially holds the haiku together as one cohesive unit.

The problem with kireji is that it has no direct comparison in English. The Japanese language essentially has vocalised punctuation, something we don’t have, instead we try to substitute it with our own punctuation which does not always achieve the same results. Another method to achieve kireji in English is to create an obvious juxtaposition between two sections of the poem; conflict and resolution, cause and effect, statements and reactions, these kinds of things.

Let’s take a look at another example, this time by Kobayashi Issa.

“Everything I touch

with tenderness, alas,

pricks like a bramble”

Kobayashi Issa

In this example there is an accentuated moment of pause at the end of the second line, but what part of it is the kireji? If you read it carefully the first comma creates the biggest impact; if ‘alas,’ wasn’t there it would have the same effect of creating a pause while creating a turning point that connects the preceding and succeeding lines. In this example the ‘alas,’ only acts to accentuate it further and could be considered a giant kireji as a unit.

The kireji isn’t normally this easy to spot but works well at illustrating the idea.

Conclusion

There is a subtlety to haiku among their briefness that perfectly captures the ambience of a particular scene. They are a type of poem that you can appreciate in a moment and at a glance while still being a carefully crafted piece of writing. It’s these values that make these Japanese haiku poems so wonderful — no matter who writes them.

Nathan